First posted on my other

blog and now on my "literary" blog.

If you’ve never read anything by the Caine and Commonwealth prize winning author Helon Habila, the first thing to know is that his use of language is exquisite. The second thing to know is that he makes generous use of irony. Although he is a clearly political writer, he questions over-easy assumptions and political binaries. In his latest novel,

Measuring Time, Habila continues the project he began in his debut novel

Waiting for an Angel—that is to tell history through the eyes of ordinary people.

Waiting for an Angel opens in a prison setting. The imprisoned journalist Lomba is engaged in a battle of wits with the prison superintendent who is extorting poetry from his prisoner in an attempt to impress a woman. If Lomba’s story were told in a straight line, the way it might appear in his priso

n file, it would be the story of a failure: a student who drops out of university, who loses friends to madness and military violence and the women he loves to other men, a writer who never finishes his novel and whose journalistic career

is cut short by his arrest in the slums of Lagos. However, this is not the story that Habila tells. By breaking up and rearranging the linear story of Lomba’s life, he wrests control of the narrative away from an environment-determined fate. The novel starts at the end of the chronological sequence and then circles back to gather stories of other characters in Lomba’s Lagos: a young boy banished from his home in Jos for smoking Indian hemp, an abandoned out-of-wedlock mother, an intellectual in a tragic love affair with a former student turned prostitute, the daughter of a general whose mother is dying of cancer, a disillusioned woman who runs a neighborhood eatery, a man who defies the soldiers on the night of Abacha’s coup, an editor pursued by the police who refuses to go into exile, a legless tailor who dreams of bidding poverty goodbye.

While the form of Waiting for an Angel reflects the frenetic beat of life in Lagos, the small town setting of Habila’s second novel Measuring Time allows for a more meandering pace. Mamo and LaMamo are twins growing up in the middlebelt town of Keti, and they hate their father, a womanizing businessman with political ambitions. They hate him for breaking their mother’s heart before she died giving birth to them, and they hate him for his long absences and his neglect. The twins’ simultaneous desire for revenge and quest for fame ends in their separation. When LaMamo runs away in search of adventure as a mercenary soldier, Mamo’s sickle cell anemia forces him to stay at home, spending more and more time in his imagination. The narrative of Mamo’s day to day life in Keti is rhythmically punctuated by adventure-filled letters from LaMamo as he travels around West Africa. Mamo reimagines events in Nigerian history: the poet Christopher Okigbo did not die in Biafra but instead lay down his gun to travel around Africa with Mamo’s Uncle Haruna. LaMamo enacts Mamo’s imagined story, becoming a soldier-poet who reports from the Liberian war front, and his words capture the spiritual horror and the boredom of war as it is rarely recorded in international news. The twins long for the other: while Mamo imagines adventures beyond the borders of his small town, LaMamo constantly searches for reminders of home in foreign lands.

The narrative of

Measuring Time is frequently interrupted by folktales told by Mamo’s Auntie Marina, letters from LaMamo and a professor in Uganda who becomes Mamo’s mentor, excerpts from the memoir of the first missionary in Keti, his wife’s diary, and colonial reports, and the oral histories told by other characters. One of the most remarkable aspects of Habila’s prose is this inclusion of multiple genres alongside a continuous pattern of tributes to preexisting literary works. In

Waiting for an Angel, he borrows the character of the prison superintendent from Wole Soyinka’s

The Man Died and gives him some of the associations of the folkloric dodo, a dim-witted monster who is often outwitted by the youth he kidnaps. Throughout the rest of

Waiting for an Angel he references writers as varied as Ayi Kwei Armah, Ousmane Sembene, Ngugi wa Thiong’o, Franz Kafka, John Donne, and Sappho. Similarly in

Measuring Time, he bundles together Plutarch, Christopher Okigbo, William Shakespeare, Wole Soyinka, Alex La Guma, the Arabian Nights and Faust legends, as well as references to oral tales and Nigerian video films. The effect of these competing voices is to open up the boundaries between his fiction and other fictions and historical accounts that lie outside the novel. The illusion of a smooth, progressive, and abbreviated history, such as the

Brief History of West Africa that is brought to Lomba in prison (as the

Letters of Queen Victoria had been brought to Soyinka in prison) is a false one. Habila’s fictional histories play a function similar to the colonial history the

Pacification of the Primitive Tribes of the Lower Niger in Chinua Achebe’s

Things Fall Apart in which the district commissioner writes only a paragraph on a man who has been the subject of Achebe’s entire novel. Habila parallels Achebe’s fictional colonial text in Measuring Time with the missionary text

A Brief History of the People’s of Keti by Reverend Drinkwater.

It is with these “brief histories” that Habila’s project in both Waiting for an Angel and Measuring Time becomes clear. Mamo is determined to write a history that does not “cut details” as the colonial histories had—a history that tells the stories of “individuals, ordinary people who toil and dream and suffer” (MT 180). The traditional ruler’s story he has been hired to write, Mamo states, is “simply a part of the other biographies…. [that he would] eventually compile to form a biographical history of Keti. That’s what history really is, people and their lives, no matter how we try to manipulate it. It is the story of real people with real weaknesses and strengths and… not about some founding fathers and … even if we want to write about the founding fathers we shouldn’t privilege them, we should place them on par with other ordinary folks…” (225). In Mamo’s subsequent “biographical history,” he writes of his father the failed politician, and his aunt the divorced wife, placing their stories alongside the less than glorious history of the mai, the traditional ruler, of Keti. Every story has its own place alongside the others. When LaMamo returns with a revolutionary fervour reminiscent of Ngugi’s Matigari, the separate lives of the twins blend and become one—LaMamo’s panAfrican experience and his soon to be born child are given into Mamo’s safekeeping and for recording into Mamo’s history of Keti.

Such a history is not merely a radical rewrite of racist colonial histories but an empathetic window into the lives of even the unpleasant characters. The characterization of the prison superintendent in Waiting for an Angel follows Soyinka’s original caricature, but the man is given a more complex psychology. He is a man grieving for his dead wife, a father of a young son. As Lomba realizes when he meets the superintendent’s girlfriend, “The superintendent had a name, and a history, maybe even a soul” (WfA 37). While in Measuring Time, the sleepy-eyed traditional ruler of Keti and his evil vizier take on the typed characteristics of folktale or a video film, most of the characters in Measuring Time are treated with complexity and compassion. When LaMamo calls the old widows who had pursued their father all his life “shameless old women,” Mamo reminds him that “they weren’t so bad… People are just people” (MT 343). And although the missionary Reverend Drinkwater may have misrepresented the history of Keti, his family has become a part of the history of the town. The missionary’s daughters, now old women, live in Keti, tending their parents’ graves. Although they are not Nigerian, they belong in Keti. It is the only life they have ever known.

This concern with multiple perspectives on history is behind what at first glance might seem to be an editorial flaw in Habila’s two novels. When reconstructed in both novels, time doesn’t quite add up. According to the chronology given in “Mamo’s notes toward a biography of the Mai,” the number of years between the installation of the first mai by the British and the current mai should be about thirty two or three years, yet the time period is stretched from 1918 up to the 1980s (MT 238-240). The year-long planning period for the celebration of the mai’s tenth anniversary seems to turn into three. Similarly in Waiting for an Angel, the time between Lomba’s stay at the university and his imprisonment seem much longer than the actual historical tenure of Abacha’s regime. He supposedly meets and falls back in love with an old girlfriend some time after he becomes a journalist. Yet, two weeks before he is arrested (after he has worked at the Dial for two years), another girlfriend, with whom he has lived for a year, leaves him. The times between the two love affairs don’t quite seem to add up.

Placing the novels side by side gives a hint to what Habila is doing here. In

Waiting for an Angel, Habila gathers up historical events that happened along a spectrum of ten years and bundles them into the space of a week. Although Nigeria is kicked out of the Commonwealth in November 1995, in the novel, a week after this event, Dele Giwa, the editor of

Newswatch Magazine, is assassinated by a parcel bomb on the same day that Kudirat Abiola is assassinated by gunmen. Of course, historically, the two activists were killed ten years apart: Dele Giwa during the Babangida regime in October 1986 and Kudirat Abiola during the Abacha regime in June 1996. The quickening rhythm of disaster in this chapter of

Waiting for an Angel parallels the last quarter of the

Measuring Time in which Mamo falls into the hard-partying lifestyle of corrupt politicians, religious riots break out, and the quiet town of Keti goes up in flames. Time here is not a mathematical iambic pentameter that can be measured with a clock, but a living fluctuating force that lags behind and loops around to find the stories of multiple characters. It reminds me of the way time acts in Gabriel Garcia Marquez’s

One Hundred Years of Solitude or in oral tales and epics. It cannot be diagramed into a dry progression of events such as those found in

A Brief History of West Africa or

A Brief History of the Peoples of Keti but instead can only be mediated through the memories of those who experienced it. In his afterward to

Waiting for an Angel, Habila acknowledges the liberties he has taken with the chronological order of events, “[N]ot all of the above events are represented with strict regard to time and place—I did not feel obliged to do that; that would be mere historicity. My concern was for the story, that above everything else” (WfA 229).

Mamo’s story of Keti, like the story of Lomba in Waiting for an Angel, becomes in miniature the story of Nigeria—not that it can represent all the complex and multi-faceted stories of the nation, but that it offers an example of what can be written: the individual stories of ordinary people living in extraordinary times. Habila layers his work onto that of older writers such as Achebe and Ngugi who rewrote colonial history in their early works, and joins other contemporary Nigerian writers like Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie and Teju Cole whose writing seems similarly concerned with providing entry points into historical events as lived by ordinary people. Measuring Time ends with the performance of a play by church women’s group, both celebrating and mocking the appearance of the missionary Reverend Drinkwater into Keti history. Mamo realizes that through their caricatured performance, they are telling the story on their own terms, invoking a way of life much older than the colonial encounter: “They were celebrating because they had had the good sense to take whatever was good from another culture and add it to whatever was good in theirs: they had done this before when they first met the Komda, and many times before that in their travels and migrations, in times earlier than even the oldest among them could remember. This was their wisdom, the secret of their survival. This was why they were still able to laugh… each generation would bring to this play its own interpretation” (MT 382). This at root is the power of Habila’s work—the ability of humanity to laugh in the face of tragedy—the ability to undermine stories that have been told for you by telling them yourself.

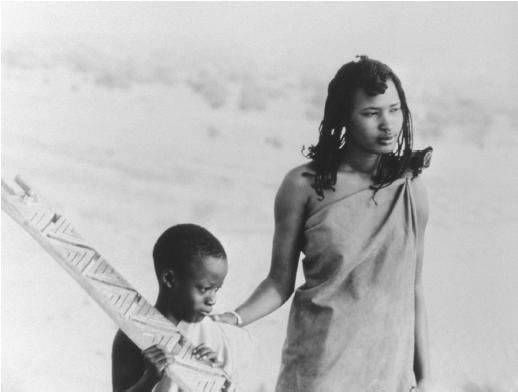

ater and greenery, while the father’s journey seems to be through the dry, brown landscape. The father’s practice is linked to death (the immolation of the chicken, the implied slaughter of the albino, the resolve to kill his son) while Nianankoro consistently preserves life: he ends the war between the Peul and their invaders, he plants the seed in the womb of the “barren” Peul woman. The flowing of the milk over the mother’s head is visually paralleled by the flowing of the waterfall over the son and his wife; it becomes a cleansing symbol of new life. It is not long after this ritual cleansing that the uncle tells Nianankoro that “if I were to die today and you too, our family would not perish. Your wife is pregnant with a son, who is destined to be a bright star.”

ater and greenery, while the father’s journey seems to be through the dry, brown landscape. The father’s practice is linked to death (the immolation of the chicken, the implied slaughter of the albino, the resolve to kill his son) while Nianankoro consistently preserves life: he ends the war between the Peul and their invaders, he plants the seed in the womb of the “barren” Peul woman. The flowing of the milk over the mother’s head is visually paralleled by the flowing of the waterfall over the son and his wife; it becomes a cleansing symbol of new life. It is not long after this ritual cleansing that the uncle tells Nianankoro that “if I were to die today and you too, our family would not perish. Your wife is pregnant with a son, who is destined to be a bright star.”