In Achille Mbembe’s essay, “At the Edge of the World: Boundaries, Territoriality, and Sovereignty in Africa,” he engages with Braudel’s notion of temporal pluralities—that there are multiple kinds of time: “temporalities of long and very long duration, slowly evolving and less slowly evolving situations, rapid and virtually instantaneous deviations, the quickest being the easiest to detect” and “the exceptional character of World Time” (22). In Braudel’s thinking, world time has control over certain spaces, while others completely escape it. Mbembe relativizes Braudel’s thesis by maintaining that 1) temporalities overlap and interact with each other. They are not completely segregated. 2) There is no place completely separate from “world history,” but there are modalities, or categories in which it is manipulated to fit with local variables (23).

Abderrahmane Sissako’s 1998 film Vie sur terre (Life on Earth) illustrates Mbembe’s idea of temporal modalities and plays with the idea of “world time.” In the village of Sokolo, everyone knows what is going on in the outside world. In the local radio station, ancient radios are interspersed with glossy images cut from foreign magazines: including an image of a happy Prince Charles, Princes Diana, and baby Prince William frozen in time years after Diana’s divorce and death. A young man enthuses over a Japanese SUV in a magazine, and tells the photographer about the doors in Abijan that open by themselves. The young men sit all day listening to RFE radio from France, on which the millennium celebrations in New York, Paris, and Tokyo are reported. The voice on the radio says: “Not all countries have the same time, but those that do are celebrating the millennium.” This statement seems to get at the heart of the film in which global knowledge from the outside permeates the village, but in which knowledge from the village cannot be found on a larger global scale or even in the next village. One suspects that in the nearby villages similar young men listen to RFE and know world news but do not know the news of the neighboring village.

This is illustrated in the multiple characters who try to make phone calls but cannot get through. The dusty sign “telephone a priority for everyone” is ironic. While on the “outside” everyone may have a telephone, this is obviously not the case here, where the telephone serves as the metaphor for the “inability to speak” to the outside world. The soldier cannot get through to his camp. Nana cannot get through to a nearby town. The character played by Sissako attempts to make a phone call to Paris, but it is misdirected to London. The characters wait for people to call them back—since the telephone seems to work like the news, only in one direction. When the person from Paris gets through the disabled postmaster leaves the phone off the hook and sets off on his crutches to find Sissako. He disappears into the village, and nothing more is heard of him or of the call. Information seems to be lost in a time warp.

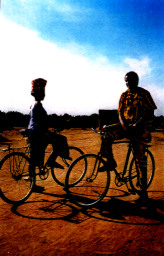

The gap in communication and time is contradicted by the visual movement of the film. Far from being a place where “nothing happens.” Sokolo is characterized by constant bi-directional movement. If communication moves soley from the outside to the inside, the daily activities of the villagers movement of the village crisscross. Throughout the film, if a bicycle or other vehicle passes from the right to the left of the frame, a canoe or a donkey cart, or another bicycle will cross from the left to the right. The visual back and forth of the film performs multiple times on a small scale, what Sissako does on a large scale with the form of the film. The initial opening in the French supermarket fades into the large tree (representative perhaps of history?), and then the old man reading the letter from Sissako in Paris. If the film opens with communication pointed toward Sekolo, The rest of the film is an outward response to this initial letter from the outside. The man dictating the letter to his brother in Paris does on a small scale what the entire form is doing: taking the news of Sokolo to the outside.

At the very end of the film, Nana, with a determined set to her face, pedals off on her bike, apparently to the neighboring town she has been trying to call. If she cannot get through on the phone, she will go there in person. This resolve to take herself there is what Sissako has done with the film: he has brought the village, like a letter, into the global discussions of the millennium, where its existence in time can no longer be ignored.

Work cited in addition to the film:

Mbembe, Achille. trans, Steven Rendall. “At the Edge of the World: Boundaries, Territoriality, and Sovereignty in Africa” in Globalization. Ed. Arjun Appadurai. Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2001.

Work cited in addition to the film:

Mbembe, Achille. trans, Steven Rendall. “At the Edge of the World: Boundaries, Territoriality, and Sovereignty in Africa” in Globalization. Ed. Arjun Appadurai. Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2001.

For more information, see also this interview with Sissako.

No comments:

Post a Comment