Mahamat-Saleh Haroun. Bye, Bye Africa. 1999.

In his 1999 film Bye, Bye Africa, Mahamat-Saleh Haroun questions the role of African cinema in everyday African life. It appears that the models his semi-autobiographical protagonist, the expatriated filmmaker Haroun takes for making films (or those of the filmmaker he plays in the film) have more to do with French ideals than with what people in Chad actually want to see. When he returns home after years in France to mourn his mother, Haroun's father questions the use of his profession, noting that if he had studied medicine, he could have saved his mother. Referring to the film that Haroun made about “some European (Freud),” he asks “What’s the use of cinema,” claiming that “Your films are not made for us. They are made for Europeans.”

In his 1999 film Bye, Bye Africa, Mahamat-Saleh Haroun questions the role of African cinema in everyday African life. It appears that the models his semi-autobiographical protagonist, the expatriated filmmaker Haroun takes for making films (or those of the filmmaker he plays in the film) have more to do with French ideals than with what people in Chad actually want to see. When he returns home after years in France to mourn his mother, Haroun's father questions the use of his profession, noting that if he had studied medicine, he could have saved his mother. Referring to the film that Haroun made about “some European (Freud),” he asks “What’s the use of cinema,” claiming that “Your films are not made for us. They are made for Europeans.”

Haroun attempts to explain to his father the need to define himself in film: “The white man’s land is nice, but not yours. The day you think you belong you lose something.” His response indicates that his homecoming is a way of re-discovering his Chadian identity. After watching the footage of his deceased mother, he quotes Godard: “Cinema makes memory.” His decision to make a film in tribute to his mother indicates that he is retracing his steps—attempting to capture his memories of the events that have formed his life and his art. When he says “to forget my grief, I’ll make a tribute to the one who gave me life,” he simultaneously pays tribute to his literal mother and his symbolic mother, the dying cinema in Chad.

However, as is indicated in the opening scene that shows him answering a long distance phone call while in bed with a white woman, his ten years in Europe without traveling back home seem to have turned him into a European. He no longer seems to understand life in Chad. He walks around with the video camera, shooting everything he sees, as if he were a European tourist. When the man outside the theatre attacks him, he shouts “He is stealing our image,” and although Haroun thinks the man is mad, the situation is more complex than Haroun imagines. In his films oriented to a European audience, his images of Chad do become a kind of exploitation—stealing images of a crumbling infrastructures to offer the West as confirmation of Africa’s incapacity. The radio clip from Thomas Sankara’s speech about the imperialism of the West and the dependency that foreign aid creates reinforces Haroun’s ambiguous position. Even the title of his proposed film, Bye, Bye Africa, addresses Chad from a distance, homogenizing the individual experiences of a local place into the large abstract “Africa.” He is addressing Chad, at best, reflexively—over his shoulder.

Like a European tourist, Haroun does not recognize any responsibility he may have to the people whose images he captures in his films. When he asks the women trying out for a part in his film if they will agree to appear naked, he draws more from European/ American ideas of what cinema should show than from aesthetics born out of the cultures of Chad. When one of his former actresses tells him that her husband would object to her playing naked, he indicates that if she were a serious actress she would be willing to give up her husband for her career. Although she leaves with an ironic regret, another auditioning actress leaps straight to the heart of the problem: “Are you Chadian?” she shouts before storming out.

As his friend Garba indicates, in Haroun’s desire to make “real cinema,” he has forgotten the realities of life in Chad. Haroun seems little aware of how his film on AIDS affects the life of Isabelle: near the end of the film she tells him “Reality scares you. You hide in films. I am not a fictional character. I exist.” His careless use of Isabelle in the film overlaps with his careless use of her in real life. Indeed, over the course of the film he begins to learn what Isabelle warns him about, viz. that “Cinema is stronger than reality”—a lesson that is reinforced by the blurring of boundaries between a fiction film and a documentary. It is as if by acting an AIDS victim in his film, Isabelle has actually contacted a deadly disease that will kill her in the end. Indeed when they meet again after ten years, she foreshadows her own death “I’m finished Haroun. Your film killed me.” Her theft of his camera to film her final words, therefore, brackets her encounter with him: her troubles begin and end on film.

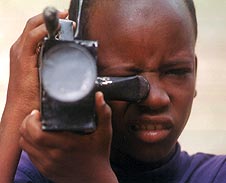

Within Bye, Bye Africa, there are hints that although Haroun is unable to square his own training and technique with the needs of his African audience, film is certainly not dead in Chad. Although the cinema halls are in a state of decay, the video clubs are bursting at the seams, and though people seem to express a nostalgia for the good old days of cinema, the stories they like are action films—not the worn out prints from the cinemas or the films about Freud that Haroun has made thus far. If we read Bye, Bye Africa as a tribute to his two mothers, the actual woman and the cinema, his final recognition of his persistent nephew who follows him about with his skillfully crafted toy camera is symbolic for his realization that though one loved one may die, there are others living now who must be appreciated. The camera that he gives to his nephew near the end of the film implies that the next generation will appropriate film technology to record that which is around them, their everyday life. And although he bids Chad, Africa, farewell, his nephew chases him down the street, filming him. In this conciliatory gesture, the new young filmmaker acknowledges that the expatriated Haroun, too, is now a part of the Chadian reality: he records him as he leaves, as if to say, you will not be so easily forgotten.

No comments:

Post a Comment