Yeelen (1987, Mali) directed by Souleymane Cissé

The visual patterning in Souleymane Cissé's film Yeelen reinforces the coming of age, journey motif and the parallel structure of the myth. Nianankoro’s mother sends him on a journey in which he travels from childhood to adulthood and must struggle against his father to find his own destiny. The struggle against the father counters the reformative new with the corrupted older tradition.

The visual patterning in Souleymane Cissé's film Yeelen reinforces the coming of age, journey motif and the parallel structure of the myth. Nianankoro’s mother sends him on a journey in which he travels from childhood to adulthood and must struggle against his father to find his own destiny. The struggle against the father counters the reformative new with the corrupted older tradition.

While Yeelen tells the story of Nianankoro’s journey from “childhood” to “adulthood,” from mother to wife, the pursuit and the chant of the father is a motif that stitches together Nianankoro’s journey. The father travels together with his two slaves and his post, seemingly driven by an anxiety that Nianankoro and his mother are trying to change tradition. And if tradition is defined as secretive purity, as Nianankoro’s (good) uncle implies when he explains that his twin blinded him when he asked him to “reveal secrets so that all might benefit,” then Nianankoro’s father has cause for worry. Although Nianankoro’s (bad) uncle disrespectfully dismisses the Peul king as a “little Peul” apparently because of their inability to do magic, the Bambara “nation” survives through Nianankoro’s marriage with the Peul woman. And at the end it is the Peul woman who is left to pass on the story of the “Bambara” nation to her son. Nianankoro penitently offers his life to the Peul king because he had “broken our laws” by sleeping with the king’s young barren wife; however, during the previous scene in which this sin is implied, the lovers seem lost in a trance comparable to that that the old men go through during their ritual. The smiling face of the girl appears to Nianankoro disembodied and surrounded by the same white light that blinds father and son in their final battle. The union of the Peul woman and the Bambara man seems to be fated, the breaking of the old law inevitable in order to bring about the new order. The Peul king seems to realize this, when Nianankoro’s uncle comes looking for him. Although Nianankoro and his new wife had left the Peul camp in shame, the Peul king refuses to betray him, saying that he had “helped us.”

The old laws have become corrupt. The father’s killing of the albino, the exploitation of his slaves, the blinding of his own twin brother, and the uncle’s arrogant dismissal of the Peuls contrasts with Nianankoro’s solitary journey and his ready willingness to help the Peuls who had initially taken him into captivity. After the mother tells Nianankoro how terrible his father is, we later find out that the father is pursuing Nianankoro because the mother has stolen his tools of sorcery. The mother’s theft counters the father’s cruelty. The importance of these two women (the mother and the wife) to Nianankoro also contrasts him with the father, whose world seems almost entirely made up of old men and young male slaves. Nianankoro seems to perform as the instrument of a more inclusive feminine world. The mother tells him his history and sends him on his quest. His wife picks up the story to pass on to their son. The “mothers” challenge the secretive authority of the “father,” while also revealing the chain of continuity in which the story is passed from mother to son.

Visually, the film takes us from the dark enclosed space of the mother’s house to the large empty savannah landscape that Nianankoro and his father travel across. Her prayer for Nianankoro’s safety, submerged as she is in watery purples and blues, parallels the end of his journey to the mountains and the long purple horizon as his uncle tells him of his origins. The framing of the purple horizon near the top of the shot is the same when the mother prays to the goddess of the waters “Save my son, keep him from ruin,” as it is when the uncle tells him “Last night, I saw a bright light cross the sky…. The catastrophe will spare your family.” The mother and the uncle are linked in their desire to preserve and share life; the father’s single minded purpose seems to destroy it. The uncle tells him that he became separated from his twin, when he asked him “to reveal secrets so that all might benefit. In a rage, he rushed out with the wing of Kore and blinded me.” It is significant, therefore, that the mother and the uncle are identified with w

ater and greenery, while the father’s journey seems to be through the dry, brown landscape. The father’s practice is linked to death (the immolation of the chicken, the implied slaughter of the albino, the resolve to kill his son) while Nianankoro consistently preserves life: he ends the war between the Peul and their invaders, he plants the seed in the womb of the “barren” Peul woman. The flowing of the milk over the mother’s head is visually paralleled by the flowing of the waterfall over the son and his wife; it becomes a cleansing symbol of new life. It is not long after this ritual cleansing that the uncle tells Nianankoro that “if I were to die today and you too, our family would not perish. Your wife is pregnant with a son, who is destined to be a bright star.”

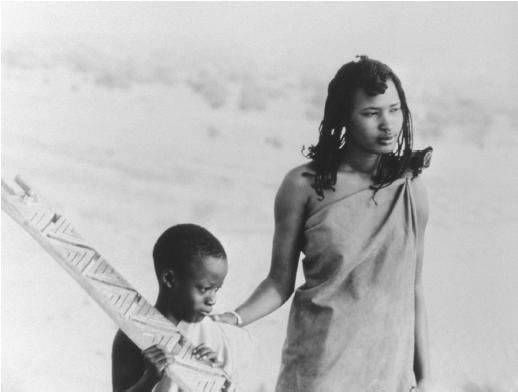

ater and greenery, while the father’s journey seems to be through the dry, brown landscape. The father’s practice is linked to death (the immolation of the chicken, the implied slaughter of the albino, the resolve to kill his son) while Nianankoro consistently preserves life: he ends the war between the Peul and their invaders, he plants the seed in the womb of the “barren” Peul woman. The flowing of the milk over the mother’s head is visually paralleled by the flowing of the waterfall over the son and his wife; it becomes a cleansing symbol of new life. It is not long after this ritual cleansing that the uncle tells Nianankoro that “if I were to die today and you too, our family would not perish. Your wife is pregnant with a son, who is destined to be a bright star.” The catastrophe that the uncle predicts comes about. The father and son destroy each other in a battle of light, and leave behind them a landscape that seems completely devoid of life—the mother and son wander through dunes of sterile sand. However, rebirth is symbolized in the ostrich eggs that the boy uncovers in the sand. The mother and son leave the ostrich eggs in place of the wing, symbolizing the birth of a new tradition out of the curse of the old. Told history by his mother, Nianankoro’s son, “the bright star” will begin his own quest for light.

5 comments:

Great piece.Ur critique of this film evokes romantic feelings and I wish I did see the film.Notwithstanding,I know that Francophone west Africa are the best lettered and film makers.The late greats such as Guinea's Camara Laye who was the first African literary genius and Mali's Ousmane Sembene,the father of African cinema,attests to this.

Curiously,northern Nigeria has the biggest cinema afficionados in Nigeria e.g Kwararafa cinema in Jos,Marhaba in kano and Lamido in Yola,Adamawa.I have exhibited films in this arenas and also in Dankasawa cinema in Maradi and Ngazargamu in Zinder(both in Niger republic),and I see similarities in their appreciation of cinema/film and its role in society.Unfortunately,our British colonialist masters and their conservatism did not allow us to grow philosophically and artistically,unlike the liberal french.

Coincidentally,I also have a script I intend to shoot soon titled 'FULAKO' and it majors on similar themes like the above film.For one,it features peulh culture and am happy to point out that peulh is a race that covers most of west Africa(fulani in Nigeria).

'FULAKO' is a peulh term for 'reserve' and it encapsulates 'etiquette'.I intend to use the film to show African forms of conflict resolution/prevention.To take a cue from your critique,in peulh society(as in most African societies),there is a phenomoenon called 'wife stealing'.The eloped couple must run and hide for at least a year.Only then can they be pardoned and if they are discovered before this time elapses,the wronged husband or suitor will take his revenge on the culprit.

Looking forward to more correspondence from you,Talatu.

Jinni,

thanks so much for your comment! I will try to purchase and bring a copy of Yeelen to Nigeria in a few months, and you can watch it at this time.

I'm not sure I would necessarily romanticize French colonialism. Manthia Diawara points out in his book _African Cinema: politics and culture_ that many of the Francophone films were constrained and coopted by a dependency on French funding and insistance on "art house" rather than commercial distribution. (For example, Ousmane Sembene struggled with the French producer of his 1969 film _Le Mandat_, who required him to shoot in colour, instead of his preferred black and white, and halted production when he refused to shoot sex scenes (Diawara, 1992, 32). Additionally, the Bureau had refused to fund his first feature film La Noire de… (1966), which portrays a young Senegalese girl who goes to France to continue her position as a nanny and becomes the domestic slave of her French employers. However, the Cooperation did buy the distribution rights for the film, thus attempting to maintain control over how and where it was seen (26). Additionally, French aid to African filmmaking benefitted the French economy by employing French cameramen, editors, and lab technicians.

Critic Roy Armes argues that, while ostensibly framed as assistance, the kind of support the Cooperation offered African filmmakers was "a typical example of an aid programme where the money returns to the donor nation and does nothing to create an infrastructure in the recipient nation… Certainly this is a neutered cinema from which any real critique of French neocolonialism or African corruption must of necessity be absent. It is ostensibly a cinema of cultural identity, but the definition of this identity is distinctly limited in social and political terms." (2006, 55)

At the same time, while recognizing the ways in which French aid did affect the style, editing, and distribution of the films, it is true that the Francophone filmmakers have put together an impressive body of work, which I think SHOULD be viewed alongside contemporary work in digital media that you and other Nigerian filmakers are doing.

My argument is that you and other Nigerian filmmakers are accomplishing what Francophone filmmakers were not able to accomplish by employing and distributing at the grassroots level within Africa for a popular audience, rather than merely to the educated elite and a limited art house/festival audience.

Thanks again for you comment, and I'll look forward to continuing our conversation!

t-c

Point noted,thanks.

I just watched this film and scanning around for reviews and largely bieng dissapointed by the narrowness of scope, yours was the first I came across, that resonated what I saw and felt in the film and more. I am a big film fan but sadly I have no knowledge of African cinema. Which I soon hope to rectify. I look forward to perusing your blog and to more fine reviews like these. Cheers

Joseph,

Thank you for your kind words. I'm glad you enjoyed the review and wish you luck in your African film watching!

t-c

Post a Comment