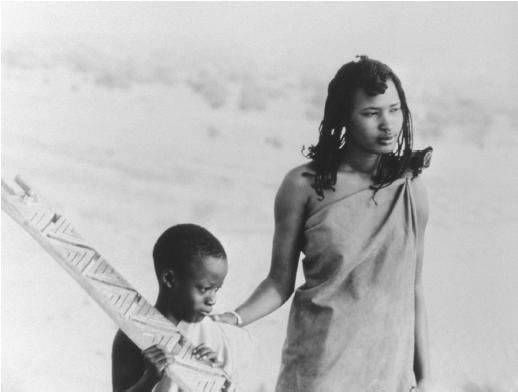

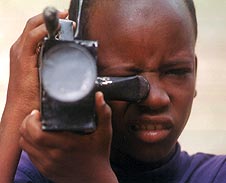

I was recently reminded of this paper I presented at the African Studies Association conference in 2006. I'm hoping to work more on this paper and include an analysis of Sani Mu'azu's recent film Hafsah. (I will include images of the handout I passed out at the conference if I can get the photos to upload.)

Mutum Duka Mod’a Ne: HIV as Transformative agent in Hausa Novels and films

In Abubakar Imam’s classic Hausa novel, Ruwan Bagaja, published in 1934, the character Alhaji Imam tells the story of his cyclic quest for the water of cure. Leaving home, Alhaji sets out on a mission to avenge his stepfather who had been mocked and shamed when he told the king that the magical water of Bagaja would cure his chronically ill son. Alhaji journeys for many years until he finds the curative water, returns to the village, and cures the prince who had been languishing since Alhaji left. A journey that began in shame ends in glory and healing, the young boy who left the village has been transformed into a successful man—the life disrupted by the prince’s illness and Alhaji’s departure is brought back into balance. This transformative quest structure, which has its origin in even older Hausa folktales, has continued in contemporary Hausa literature, which often shows how shameful circumstances may be redeemed. Imam’s symbolic search for the “water of cure” is especially significant in looking at recent Hausa novels and films that deal with the HIV virus. While other contemporary narratives that deal with societal ills end with the “cure,” HIV takes on symbolic meaning that complicates the cycle of redemption found in many earlier literary structures. I am specifically interested in how HIV has entered the social imagination, and the multiple ways in which a “disease without a cure” is conceptualized.

Social ills seen as contributing to HIV: forced marriages and hawking goods on the street, which drive girls into sex work; the neglect of the poor and sick by the wealthy; the outwardly-respectable alhaji who secretly preys on young girls: all of these negative aspects of society are censured in other recent novels and films. Within these critiques are the seeds of reform, illustrating how misfortunes can be redeemed or “cured.” In Balaraba Ramat Yakubu’s novel Wa Zai Auri Jahila, the heroine Zainabu is able to overcome her traumatic forced marriage by running away, seeking education, becoming a successful nurse, and ultimately marrying her childhood sweetheart who had originally refused to marry her because of her lack of education.[1] In this model, even great sins may be redeemed. In Sani Danja’s film Jarida (Mai Tsada) a woman destroys her family in her greed for a large contract, by following the instructions of a boka (a magician) to sleep with her drunken son-in-law. After the death and disaster that follows, she redeems her deadly sin by becoming a teacher in a girl’s Q’uranic school and warning the children against greed. The revelation of the sin acts as a purging process out of which can be born a new beginning.

The introduction of HIV in certain Hausa films and novels fits into these pre-existing models. In Sani Danja’s NGO sponsored Jan Kunne, the once promiscuous Babangida reforms and begins to go around to villages educating people about HIV. His wife Mariyya is able to overcome the abuses she suffered as a child-street hawker and the stigma she initially suffered as a person living with HIV by becoming the Hausa ideal of a virtuous, respectable wife and mother. Their child continues their legacy by growing up to be an HIV-AIDS activist. Arguably the introduction of the disease into this family’s life has worked as an instrument of transformation. Although their lives are shortened, they are richer and fuller than they were before their encounter. Similarly in Saliha Abubakar Abdullahi’s novel Ba A Nan Take Ba, Namlat is able to overcome the trauma of her earlier abusive marriage and the stigma of HIV to become a counselor at a hospital, advising other HIV-positive people who have gone through problems similar to her own. Although she refuses to marry the HIV-negative man who swears he will sacrifice his life for her, this event merely emphasizes her ability to make her own decisions and a life independent of any man’s protection. She becomes a heroine very similar to those found in the fiction of feminist writer Balaraba Ramat Yakubu, whose female characters overcome patriarchal oppression to become prominent actors in society. As the Hausa proverb that I chose for the title of this paper states: “Mutum duka mod’a ne: sai an danna shi, kana ya debo ruwa.” “Every man is like a drinking gourd; it is not until he is forced down that he will bring up water.”

While the works I’ve described above support the idea that HIV is incorporated into the redemptive quest structure, becoming a symbol of regeneration rather than of destruction, other works complicate this overly optimistic formula. In other novels and films, HIV is seen as a symbol of judgment for a sinful lifestyle, or an uneasy indication of a modernity in which known ways of dealing with social problems are disrupted. Although I’m interested in how NGO-narratives have been adapted to Hausa literary conventions, this summer while in Kano for predissertation research I became much more intrigued by the way HIV has entered the social imagination—the many different ways HIV is perceived, rather than just the authorized versions.

A theme that emerges over and over again in films and novels is that of HIV disrupting this cycle of redemption. The novels and films that began to sweep across Hausaland in the 1990s focused on the powerful force of love in conquering and reforming the corrupted values of their elders. In Ado Ahmad Gidan Dabino’s bestselling novel In da so da Kauna, the heroine Sumayya jumps in a well when her parents force her to marry a corrupt businessman, instead of the virtuous but poor young man that she loves, Muhammed. Her controversial revolt is justified as necessary for the reform of a system in which money has become more important than character and girls have become pawns in the economic schemes of their relatives. The suicide does not succeed, and eventually the love between the two sweethearts overcomes all obstacles. The Hausa ideal of balance is achieved through the passionate Sumayya with her ties to the earth, and the rational Muhammed with his invocation of Islam. In da So da Kauna is one of the most famous of a genre of Hausa novels in which love plays such an important part that they are called littattafan soyayya, novels of love. Love becomes a symbol for healing and balance in a society imbalanced by corruption.

In many of the novels dealing with HIV, however, this symbol of love is complicated. Lovers are not able to marry because of the intrusion of the disease, which is often associated with earlier acts of immorality. In Sa’adatu Baba Ahmad’s novel Mu Kame Kanmu, the young girl Sugaira is madly in love with the sophisticated Marwan, but after he relates the story of his wild life before he met her and confesses that he has AIDS, they are not able to continue with plans to marry. In the film Zazzabi, a man falls in love with the beautiful daughter of a doctor. After the doctor is mysteriously murdered, it finally comes out that the daughter’s fiancé discovered that her father was the same doctor who told him that he was HIV positive. What initially seems like a charming love affair turns into a gruesome string of murders and attempted murders, as he dispatches anyone who begins to suspect him. The stereotype of the vengeful AIDS patient, who tries to infect as many people as possible, seen in both Hausa and English Nigerian creative works—here takes on an even more complex form—the AIDS patient who must eliminate those who know his secret and will prevent him from living a normal life. After his secret is revealed, the girl eventually returns to a former boyfriend, only to have him tell her that he too has AIDS, which he had contracted in an imprudent encounter with a prostitute years earlier. The redemption of past mistakes through love, in these cases, is complicated by the existence of HIV. Zazzabi reinforces the feeling that HIV has halted the forward progression of the narrative; it is like a scratch in a record that causes the needle to jump backward and start over again. While the Hausa ideal is balance, this film is left profoundly unbalanced. Forces of social regeneration are no longer working. The girl is left fatherless, loverless, and alone.

Although in Jarida (Mai Tsada), the woman who got pregnant by her son-in-law was able to redeem herself by becoming a Quranic teacher, the redemption of similar “fallen women” in many of these tales is made more complex by the introduction of HIV. In Ibrahim Sheme’s novel ‘Yartsana, Asabe runs away to become a prostitute after being forced to abandon her sweetheart and marry another whom she does not love. After years of unconventional adventures, she meets her old sweetheart, repents of her lifestyle, and is ready to start a new life. Her desire to be reintegrated into the sphere of Hausa moral society is heightened by seeing how her friend Bebi has made the transition from prostitute to virtuous wife and mother. Unfortunately, soon after her change in lifestyle, Asabe finds that she has contracted AIDS. Instead of being rewarded for her repentance, she dies abandoned and alone. Like other Hausa quest narratives, she has come full circle back to the village she had run away from, but hers is not a triumphal arrival like Alhaji Imam’s but one of defeat. Similarly, in the film Bakar Ashana, a respectable young man wants to marry the prostitute Zainab. Enchanted with the idea of becoming a proper wife, Zainab goes through her iddah waiting period before marriage, wandering through the brothel in a hijab, devoutly praying, and giving advice to the other prostitutes; however, before she can marry her fiancé, she grows ill with AIDS and dies. The cycle of redemption is thwarted by the introduction of the incurable disease. Instead the cyclic movement of the tale seems one of despair. In the film, Bakar Ashana, I’ve just described, the story is framed between two deaths: a prostitute dies at the beginning, followed by a party scene with the prostitutes dancing. From these two extremes, the narrative emerges: the Cinderella tale of a woman who transforms from prostitute to virtuous woman. However, this transformation ultimately seems to make no difference. Following another scene in which the prostitutes dance, the film closes with Zainab’s death. The progressive and hopeful narrative is enclosed between the double wall: the “shameless” dance of the prostitutes and death. While Zainab gasps out a Q’uranic verse on her deathbed, she is unable to escape the disease that marks her identity as a prostitute.

The novel ‘Yartsana and the film Bakar Ashana are unique in that they explore somewhat sympathetically the lives of two prostitutes, investigating their emotions as well as the exciting life they are caught up in. Most of the other novels and films I read reduce this complexity to flat symbolism. Prostitutes become stand-ins for the disease itself, providing cameo appearances to explain how HIV enters the domestic sphere and captures “innocent” victims.

Although HIV is usually associated with activities that take place outside the sphere of Hausa morality, these novels and films demonstrate the anxiety that the disease of outside, a disease of corruption, is infiltrating the inside of the domestic space. In Saliha Abubakar Abdullahi’s novel Ba a nan take ba, a virtuous wife is infected with the disease by her husband who drinks, smokes, and frequents ladies of the night. In Guduna Ake Yi, a young woman describes how her father, a virtuous and successful businessman, was infected with HIV after a corrupt doctor gave him a blood transfusion without testing the blood. Her father then passes it on to her mother, who passes it on to their newborn daughter. In the film Waraka, a Fulani herder sleeps with a prostitute while in town to trade cattle. Much later, he infects his little sister when he cuts himself on a broken bottle, which she immediately cuts herself on as well. Other than characters in NGO-sponsored films, who have counselors and support groups, those who have contracted the disease through interactions that fall outside the sphere of proper Hausa morality aren’t presented with much of a second chance in most of the other films. The cattle herder who accidentally infects his innocent sister dies, racked with coughs; the prostitutes die before they can become respectable. Intended marriages, (the ideal state of balance in Hausa society) are halted.

But while death might be viewed by the Hausa audience as a fitting punishment for those who did not heed laws of proper behaviour in life, there are hints at redemption after death. Although most of the films dealing with HIV end in death, the film Waraka provides an alternate interpretation of what that death means. The innocent girl who contracted HIV through being cut with glass bloodied by her infected brother is comforted by the words of her lover reminding her about Paradise. The ultimate cure, he tells her, is not in this life but in the next. The end of the cycle—the restoration of balance might not be fulfilled in this life, but it will be after death. The producer of the film, Ahmad Sarari, told me that he centred the story around an “innocent victim” to combat the stigma that one could only have HIV if one was a prostitute. However, the comfort he imagines in the words of Q’uranic poetry, also can be found for the characters who repent of sins before they die. Zainab in Bakar Ashana dies with the verse from the Q’uran on her lips. Other characters appeal to God and swear to live virtuously the rest of their days. In this formulation, HIV might be a judgment, but it is also a chance for repentance and renewal, if not in this life, the next.

Although the majority of these works ended with the death of the characters infected with HIV, I am the most intrigued by the novels and films that end with their characters still alive—the brooding young men in Zazzabi and Mu Kame Kanmu who have to tell their sweethearts why they cannot marry; the infected wife turned counselor in Ba a Nan Take ba. Instead of neatly tying off the plot with death, these living characters leave open multiple possibilities of how to imagine a life with HIV. (HAFSAH-2007-produced and directed by Sani Mu'azu takes this in a particularly interesting direction. I will expand this later....) The cycle is left open—unfinished. Out of the four novels on HIV that I’ve mentioned here, three of them take the form of the protagonist telling their story to another listener, much like the storytelling competition in Ruwan Bagaja, in which Alhaji tells of his quest for the healing water of Bagaja. The first person narration of these stories similarly becomes a quest for healing: by telling their story, they live on beyond the pages of the novel and beyond their own expected deaths. The readers attention is drawn to the story of their lives told in their own words, not to their objectifying death. Brian Larkin writes that “the mass culture of soyayya books [novels of love]… develops the process of ambiguity by presenting various resolutions of similar predicaments in thousands of narratives extending over many years. By engaging both with individual stories and with the genre as a whole, narratives provide the ability for social inquiry” (Larkin, “Indian Films,” 28). This process is continued in Hausa film. Since the pool of actors is relatively small, the same actors appear in many different stories that are variations on a theme. In the films with HIV narratives, it is especially striking to see an actor like Sani Danja who played an HIV patient turned activist in Jan Kunne playing a stricken lover who cannot marry his girlfriend because he is (again) HIV+ in the film Zazzabi. In the process of telling many stories, Hausa novelists and filmmakers probe the boundaries, imagine multiple scenarios, various possibilities. Redemption, here, comes not in a formula, not in one specific “water of cure,” but in the exploration of many lives, in the stumbling and imperfect attempts at negotiating an incurable disease through one story, one quest, after another.

WORKS CITED:

Hausa Novels:

Abdullahi, Saliha Abubakar. Ba A Nan Take Ba. Zaria: Hamden Press, 2004.

Ahmad, Sa’adatu Baba. Mu Kame Kanmu. Kano: 2003.

Gidan Dabino, Ado Ahmad. In da so da k’auna 1, 2. Kano: Nuruddeen Publication, 1991.

Imam, Alhaji Abubakar. Ruwan Bagaja. Zaria: NNPC, 1966.

Sheme, Ibrahim. ‘Yartsana. Kaduna: Informart Publishers, n.d.

Sulaiman, Fauziyya D. Gudu Na Ake Yi: 1, 2. Kano: 2006.

Yakubu, Balaraba Ramat. Wa Zai Auri Jahila? Kano: Gidan Dabino Publishers, 1990.

Hausa films:

Babinlata, Bala Anas, dir. Waraka: the Cure. Kano, Klassique Films, 2005.

Bala, Aminu, dir. Bakar Ashana. Kano: Bright Star Entertainment, n.d.

Belaz, S.I. dir. Zazzabi. Kano: Sa'a Entertainment, 2005.

Danja, Sani Musa, dir. Jan Kunne 1,2, 3. Kano: 2 Effects Empire, 2002-2004.

_________________. Jarida (mai Tsada) 1, 2. Kano: 2 Effects Empire, 2004 and 2005.

Critical Works:

Larkin, Brian. “Indian Films & Nigerian Lovers: Media & the Creation of Parallel Modernities” Readings in African Popular Fiction. Ed. Stephanie Newell. Oxford: James Currey, 2002.

Whitsitt, Novian. “Islamic-Hausa Feminism and Kano Market Literature: Qur’anic Reinterpretation in the Novels of Balaraba Yakubu,” Research in African Literatures 33:2 (Summer 2002): 119-136.

[1] As described in Novian Whitsitt, “Islamic-Hausa Feminism and Kano Market Literature: Qur’anic Reinterpretation in the Novels of Balaraba Yakubu,” Research in African Literatures 33:2 (Summer 2002): 119-136.

Mutum Duka Mod’a Ne: HIV as Transformative agent in Hausa Novels and films

In Abubakar Imam’s classic Hausa novel, Ruwan Bagaja, published in 1934, the character Alhaji Imam tells the story of his cyclic quest for the water of cure. Leaving home, Alhaji sets out on a mission to avenge his stepfather who had been mocked and shamed when he told the king that the magical water of Bagaja would cure his chronically ill son. Alhaji journeys for many years until he finds the curative water, returns to the village, and cures the prince who had been languishing since Alhaji left. A journey that began in shame ends in glory and healing, the young boy who left the village has been transformed into a successful man—the life disrupted by the prince’s illness and Alhaji’s departure is brought back into balance. This transformative quest structure, which has its origin in even older Hausa folktales, has continued in contemporary Hausa literature, which often shows how shameful circumstances may be redeemed. Imam’s symbolic search for the “water of cure” is especially significant in looking at recent Hausa novels and films that deal with the HIV virus. While other contemporary narratives that deal with societal ills end with the “cure,” HIV takes on symbolic meaning that complicates the cycle of redemption found in many earlier literary structures. I am specifically interested in how HIV has entered the social imagination, and the multiple ways in which a “disease without a cure” is conceptualized.

Social ills seen as contributing to HIV: forced marriages and hawking goods on the street, which drive girls into sex work; the neglect of the poor and sick by the wealthy; the outwardly-respectable alhaji who secretly preys on young girls: all of these negative aspects of society are censured in other recent novels and films. Within these critiques are the seeds of reform, illustrating how misfortunes can be redeemed or “cured.” In Balaraba Ramat Yakubu’s novel Wa Zai Auri Jahila, the heroine Zainabu is able to overcome her traumatic forced marriage by running away, seeking education, becoming a successful nurse, and ultimately marrying her childhood sweetheart who had originally refused to marry her because of her lack of education.[1] In this model, even great sins may be redeemed. In Sani Danja’s film Jarida (Mai Tsada) a woman destroys her family in her greed for a large contract, by following the instructions of a boka (a magician) to sleep with her drunken son-in-law. After the death and disaster that follows, she redeems her deadly sin by becoming a teacher in a girl’s Q’uranic school and warning the children against greed. The revelation of the sin acts as a purging process out of which can be born a new beginning.

The introduction of HIV in certain Hausa films and novels fits into these pre-existing models. In Sani Danja’s NGO sponsored Jan Kunne, the once promiscuous Babangida reforms and begins to go around to villages educating people about HIV. His wife Mariyya is able to overcome the abuses she suffered as a child-street hawker and the stigma she initially suffered as a person living with HIV by becoming the Hausa ideal of a virtuous, respectable wife and mother. Their child continues their legacy by growing up to be an HIV-AIDS activist. Arguably the introduction of the disease into this family’s life has worked as an instrument of transformation. Although their lives are shortened, they are richer and fuller than they were before their encounter. Similarly in Saliha Abubakar Abdullahi’s novel Ba A Nan Take Ba, Namlat is able to overcome the trauma of her earlier abusive marriage and the stigma of HIV to become a counselor at a hospital, advising other HIV-positive people who have gone through problems similar to her own. Although she refuses to marry the HIV-negative man who swears he will sacrifice his life for her, this event merely emphasizes her ability to make her own decisions and a life independent of any man’s protection. She becomes a heroine very similar to those found in the fiction of feminist writer Balaraba Ramat Yakubu, whose female characters overcome patriarchal oppression to become prominent actors in society. As the Hausa proverb that I chose for the title of this paper states: “Mutum duka mod’a ne: sai an danna shi, kana ya debo ruwa.” “Every man is like a drinking gourd; it is not until he is forced down that he will bring up water.”

While the works I’ve described above support the idea that HIV is incorporated into the redemptive quest structure, becoming a symbol of regeneration rather than of destruction, other works complicate this overly optimistic formula. In other novels and films, HIV is seen as a symbol of judgment for a sinful lifestyle, or an uneasy indication of a modernity in which known ways of dealing with social problems are disrupted. Although I’m interested in how NGO-narratives have been adapted to Hausa literary conventions, this summer while in Kano for predissertation research I became much more intrigued by the way HIV has entered the social imagination—the many different ways HIV is perceived, rather than just the authorized versions.

A theme that emerges over and over again in films and novels is that of HIV disrupting this cycle of redemption. The novels and films that began to sweep across Hausaland in the 1990s focused on the powerful force of love in conquering and reforming the corrupted values of their elders. In Ado Ahmad Gidan Dabino’s bestselling novel In da so da Kauna, the heroine Sumayya jumps in a well when her parents force her to marry a corrupt businessman, instead of the virtuous but poor young man that she loves, Muhammed. Her controversial revolt is justified as necessary for the reform of a system in which money has become more important than character and girls have become pawns in the economic schemes of their relatives. The suicide does not succeed, and eventually the love between the two sweethearts overcomes all obstacles. The Hausa ideal of balance is achieved through the passionate Sumayya with her ties to the earth, and the rational Muhammed with his invocation of Islam. In da So da Kauna is one of the most famous of a genre of Hausa novels in which love plays such an important part that they are called littattafan soyayya, novels of love. Love becomes a symbol for healing and balance in a society imbalanced by corruption.

In many of the novels dealing with HIV, however, this symbol of love is complicated. Lovers are not able to marry because of the intrusion of the disease, which is often associated with earlier acts of immorality. In Sa’adatu Baba Ahmad’s novel Mu Kame Kanmu, the young girl Sugaira is madly in love with the sophisticated Marwan, but after he relates the story of his wild life before he met her and confesses that he has AIDS, they are not able to continue with plans to marry. In the film Zazzabi, a man falls in love with the beautiful daughter of a doctor. After the doctor is mysteriously murdered, it finally comes out that the daughter’s fiancé discovered that her father was the same doctor who told him that he was HIV positive. What initially seems like a charming love affair turns into a gruesome string of murders and attempted murders, as he dispatches anyone who begins to suspect him. The stereotype of the vengeful AIDS patient, who tries to infect as many people as possible, seen in both Hausa and English Nigerian creative works—here takes on an even more complex form—the AIDS patient who must eliminate those who know his secret and will prevent him from living a normal life. After his secret is revealed, the girl eventually returns to a former boyfriend, only to have him tell her that he too has AIDS, which he had contracted in an imprudent encounter with a prostitute years earlier. The redemption of past mistakes through love, in these cases, is complicated by the existence of HIV. Zazzabi reinforces the feeling that HIV has halted the forward progression of the narrative; it is like a scratch in a record that causes the needle to jump backward and start over again. While the Hausa ideal is balance, this film is left profoundly unbalanced. Forces of social regeneration are no longer working. The girl is left fatherless, loverless, and alone.

Although in Jarida (Mai Tsada), the woman who got pregnant by her son-in-law was able to redeem herself by becoming a Quranic teacher, the redemption of similar “fallen women” in many of these tales is made more complex by the introduction of HIV. In Ibrahim Sheme’s novel ‘Yartsana, Asabe runs away to become a prostitute after being forced to abandon her sweetheart and marry another whom she does not love. After years of unconventional adventures, she meets her old sweetheart, repents of her lifestyle, and is ready to start a new life. Her desire to be reintegrated into the sphere of Hausa moral society is heightened by seeing how her friend Bebi has made the transition from prostitute to virtuous wife and mother. Unfortunately, soon after her change in lifestyle, Asabe finds that she has contracted AIDS. Instead of being rewarded for her repentance, she dies abandoned and alone. Like other Hausa quest narratives, she has come full circle back to the village she had run away from, but hers is not a triumphal arrival like Alhaji Imam’s but one of defeat. Similarly, in the film Bakar Ashana, a respectable young man wants to marry the prostitute Zainab. Enchanted with the idea of becoming a proper wife, Zainab goes through her iddah waiting period before marriage, wandering through the brothel in a hijab, devoutly praying, and giving advice to the other prostitutes; however, before she can marry her fiancé, she grows ill with AIDS and dies. The cycle of redemption is thwarted by the introduction of the incurable disease. Instead the cyclic movement of the tale seems one of despair. In the film, Bakar Ashana, I’ve just described, the story is framed between two deaths: a prostitute dies at the beginning, followed by a party scene with the prostitutes dancing. From these two extremes, the narrative emerges: the Cinderella tale of a woman who transforms from prostitute to virtuous woman. However, this transformation ultimately seems to make no difference. Following another scene in which the prostitutes dance, the film closes with Zainab’s death. The progressive and hopeful narrative is enclosed between the double wall: the “shameless” dance of the prostitutes and death. While Zainab gasps out a Q’uranic verse on her deathbed, she is unable to escape the disease that marks her identity as a prostitute.

The novel ‘Yartsana and the film Bakar Ashana are unique in that they explore somewhat sympathetically the lives of two prostitutes, investigating their emotions as well as the exciting life they are caught up in. Most of the other novels and films I read reduce this complexity to flat symbolism. Prostitutes become stand-ins for the disease itself, providing cameo appearances to explain how HIV enters the domestic sphere and captures “innocent” victims.

Although HIV is usually associated with activities that take place outside the sphere of Hausa morality, these novels and films demonstrate the anxiety that the disease of outside, a disease of corruption, is infiltrating the inside of the domestic space. In Saliha Abubakar Abdullahi’s novel Ba a nan take ba, a virtuous wife is infected with the disease by her husband who drinks, smokes, and frequents ladies of the night. In Guduna Ake Yi, a young woman describes how her father, a virtuous and successful businessman, was infected with HIV after a corrupt doctor gave him a blood transfusion without testing the blood. Her father then passes it on to her mother, who passes it on to their newborn daughter. In the film Waraka, a Fulani herder sleeps with a prostitute while in town to trade cattle. Much later, he infects his little sister when he cuts himself on a broken bottle, which she immediately cuts herself on as well. Other than characters in NGO-sponsored films, who have counselors and support groups, those who have contracted the disease through interactions that fall outside the sphere of proper Hausa morality aren’t presented with much of a second chance in most of the other films. The cattle herder who accidentally infects his innocent sister dies, racked with coughs; the prostitutes die before they can become respectable. Intended marriages, (the ideal state of balance in Hausa society) are halted.

But while death might be viewed by the Hausa audience as a fitting punishment for those who did not heed laws of proper behaviour in life, there are hints at redemption after death. Although most of the films dealing with HIV end in death, the film Waraka provides an alternate interpretation of what that death means. The innocent girl who contracted HIV through being cut with glass bloodied by her infected brother is comforted by the words of her lover reminding her about Paradise. The ultimate cure, he tells her, is not in this life but in the next. The end of the cycle—the restoration of balance might not be fulfilled in this life, but it will be after death. The producer of the film, Ahmad Sarari, told me that he centred the story around an “innocent victim” to combat the stigma that one could only have HIV if one was a prostitute. However, the comfort he imagines in the words of Q’uranic poetry, also can be found for the characters who repent of sins before they die. Zainab in Bakar Ashana dies with the verse from the Q’uran on her lips. Other characters appeal to God and swear to live virtuously the rest of their days. In this formulation, HIV might be a judgment, but it is also a chance for repentance and renewal, if not in this life, the next.

Although the majority of these works ended with the death of the characters infected with HIV, I am the most intrigued by the novels and films that end with their characters still alive—the brooding young men in Zazzabi and Mu Kame Kanmu who have to tell their sweethearts why they cannot marry; the infected wife turned counselor in Ba a Nan Take ba. Instead of neatly tying off the plot with death, these living characters leave open multiple possibilities of how to imagine a life with HIV. (HAFSAH-2007-produced and directed by Sani Mu'azu takes this in a particularly interesting direction. I will expand this later....) The cycle is left open—unfinished. Out of the four novels on HIV that I’ve mentioned here, three of them take the form of the protagonist telling their story to another listener, much like the storytelling competition in Ruwan Bagaja, in which Alhaji tells of his quest for the healing water of Bagaja. The first person narration of these stories similarly becomes a quest for healing: by telling their story, they live on beyond the pages of the novel and beyond their own expected deaths. The readers attention is drawn to the story of their lives told in their own words, not to their objectifying death. Brian Larkin writes that “the mass culture of soyayya books [novels of love]… develops the process of ambiguity by presenting various resolutions of similar predicaments in thousands of narratives extending over many years. By engaging both with individual stories and with the genre as a whole, narratives provide the ability for social inquiry” (Larkin, “Indian Films,” 28). This process is continued in Hausa film. Since the pool of actors is relatively small, the same actors appear in many different stories that are variations on a theme. In the films with HIV narratives, it is especially striking to see an actor like Sani Danja who played an HIV patient turned activist in Jan Kunne playing a stricken lover who cannot marry his girlfriend because he is (again) HIV+ in the film Zazzabi. In the process of telling many stories, Hausa novelists and filmmakers probe the boundaries, imagine multiple scenarios, various possibilities. Redemption, here, comes not in a formula, not in one specific “water of cure,” but in the exploration of many lives, in the stumbling and imperfect attempts at negotiating an incurable disease through one story, one quest, after another.

WORKS CITED:

Hausa Novels:

Abdullahi, Saliha Abubakar. Ba A Nan Take Ba. Zaria: Hamden Press, 2004.

Ahmad, Sa’adatu Baba. Mu Kame Kanmu. Kano: 2003.

Gidan Dabino, Ado Ahmad. In da so da k’auna 1, 2. Kano: Nuruddeen Publication, 1991.

Imam, Alhaji Abubakar. Ruwan Bagaja. Zaria: NNPC, 1966.

Sheme, Ibrahim. ‘Yartsana. Kaduna: Informart Publishers, n.d.

Sulaiman, Fauziyya D. Gudu Na Ake Yi: 1, 2. Kano: 2006.

Yakubu, Balaraba Ramat. Wa Zai Auri Jahila? Kano: Gidan Dabino Publishers, 1990.

Hausa films:

Babinlata, Bala Anas, dir. Waraka: the Cure. Kano, Klassique Films, 2005.

Bala, Aminu, dir. Bakar Ashana. Kano: Bright Star Entertainment, n.d.

Belaz, S.I. dir. Zazzabi. Kano: Sa'a Entertainment, 2005.

Danja, Sani Musa, dir. Jan Kunne 1,2, 3. Kano: 2 Effects Empire, 2002-2004.

_________________. Jarida (mai Tsada) 1, 2. Kano: 2 Effects Empire, 2004 and 2005.

Critical Works:

Larkin, Brian. “Indian Films & Nigerian Lovers: Media & the Creation of Parallel Modernities” Readings in African Popular Fiction. Ed. Stephanie Newell. Oxford: James Currey, 2002.

Whitsitt, Novian. “Islamic-Hausa Feminism and Kano Market Literature: Qur’anic Reinterpretation in the Novels of Balaraba Yakubu,” Research in African Literatures 33:2 (Summer 2002): 119-136.

[1] As described in Novian Whitsitt, “Islamic-Hausa Feminism and Kano Market Literature: Qur’anic Reinterpretation in the Novels of Balaraba Yakubu,” Research in African Literatures 33:2 (Summer 2002): 119-136.